Before I launch into my (recent and past) experiences with Pac-Man, the arcade game developed by Namco, I would like to say something about this week’s reading, Chapter 7: “Video Games” from Greenfield (1984). Greenfield (ibid, p. 88) makes an important statement by saying that “children with a television background develoop a preference for dynamic visual imagery” before going to say that “visual action is an important factor in attracting the attention of young children to the television screen”; from this statement Greenfield goes on to suggest that “moving visual images” in arcade / video games is one such reason for the genres popularity – more so than those of text-based or “still visual image” games.

Greenfield (ibid, p. 89) goes on to suggest that children pick up and assimilate a lot of audio-visual information from the action sequences depicted on the TV screen. This is an important statement in that it suggests that children weaned on TV have the potential to be better at video games that those “generations socialised with the verbal media of print and radio”. A couple of thoughts struck me here: Firstly, children are surrounded by movement and colour in real life, what is depicted on the screen could be construed as being an extension of that – am I stating the obvious here? Secondly, could we possibly hypothesize that children “socialised with the verbal media of print and radio” might have an overly developed imagination? People talk of imagining how characters and scenes from a book that they are reading are “played over in their head”.

Greenfield goes on to suggest that other aspects that contribute towards the popularity of video / arcade games include:

- an active participatory role;

- a sense of active control;

- presence of a goal / task;

- automatic scorekeeping;

- audio effects;

- randomness;

- importance of speed.

Although Greenfield doesn’t explicitly express this, but we can see affective elements come into play with games such as sound (ambience) and visuals (information). The other element that Greenfield alludes to, which has been expressed by the psychologist Eric Erickson (Gee, 2007, p. 59) is the notion of “psychosocial moratorium” or a safe environment in which the user can take risks where the real-world consequences are minimal.

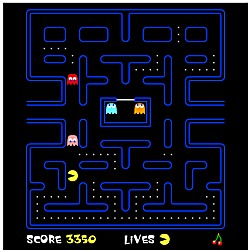

I’d like to think that I am one of Greenfield’s generation of TV kids as I was pretty much glued to that cathode ray tube during the 1970s and 1980s. However, I was also a very voracious reader during the 1980s, eschewing my paperback companion to that of the “idiot’s lantern”. It came as a surprise to me to read that Pac-Man was a lot more complex and nuanced than I first imagined. The game, superficially at least, requires the player to move around the maze, avoiding the ghosts and eating up everything in it’s path. What is not so obvious to the player is that Pac-Man operates on a number of “hidden rules” that can only be deduced from observing what is going on in the game; such as: each “ghost” has a particular characteristic behaviour and certain sections of the maze has a particular behaviour that could enhance or impede Pac-Man’s progress.

I’d like to think that I am one of Greenfield’s generation of TV kids as I was pretty much glued to that cathode ray tube during the 1970s and 1980s. However, I was also a very voracious reader during the 1980s, eschewing my paperback companion to that of the “idiot’s lantern”. It came as a surprise to me to read that Pac-Man was a lot more complex and nuanced than I first imagined. The game, superficially at least, requires the player to move around the maze, avoiding the ghosts and eating up everything in it’s path. What is not so obvious to the player is that Pac-Man operates on a number of “hidden rules” that can only be deduced from observing what is going on in the game; such as: each “ghost” has a particular characteristic behaviour and certain sections of the maze has a particular behaviour that could enhance or impede Pac-Man’s progress.

Despite playing this game on and off for a number of years, I didn’t realise that there was more to the game than meets the eye. I have always said that I couldn’t “read signs” – so this could be a cognitive dysfunction on my part? Or is it because, I prefer the medium of print to that of televisuals?

References

Gee, J.P. (2007). What Video Games Have To Teach Us About Learning And Literacy (Revised and Updated Edition). New York, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Greenfield, P.M. (1984). Mind and media : the effects of television, video games, and computers. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.